Trust is a legal arrangement where one party (the settlor) transfers assets to another party (the trustee), who then holds and manages the assets for the benefit of designated parties (the beneficiaries). It is a versatile legal structure which has been used for generations to preserve and manage wealth across generations.

A typical trust can be structured as follows:

For succession planning purposes, it is often convenient for the settlor to appoint a professional trustee to manage the trust assets. However, using a professional trustee structure may not appeal to everyone or for all kinds of trust assets.

Some limitations include:

Trustee Misfeasance: By transferring asset ownership to the trustee, the settlor relinquishes direct control over the trust assets. Occasionally, trustees may breach their duties and misappropriate trust assets. To mitigate this risk, settlors might prefer to use reputable and well-established trustees (such as bank-backed trustees), but these are often more expensive and may be unaffordable for smaller trusts.

High Cost: Professional trustees offer valuable experience but at a potentially high cost, typically a fee based on a percentage of the trust's assets. In fulfilling their fiduciary duties, trustees may need to seek professional advice, incurring additional costs.

Suitability: Trustees have a duty to manage trust assets carefully, using reasonable skill and attention. This duty extends not only to the assets themselves but also to any businesses or investments within the trust. For example, if the trust owns a significant portion of an operating business, the trustee needs to monitor how that business is run. However, professional trustees might not be best suited for handling complex, non-financial assets, making trusts less suitable for higher-risk and complex investments.

Lack of Flexibility: A trust is governed by its trust deed. When using professional trustees, settlors may have to conform to the trustee's standard operating procedures, which might not align with the settlor's specific needs.

Lack of Transparency: Once assets are transferred to the trustee, the settlor loses direct control and visibility into the ongoing management of the trust assets.

Alternatively, the settlor may appoint a trusted friend or family member as the trustee. This person may have better knowledge of the trust assets (particularly complex assets like operating businesses) and could be more suitable than professional trustees in some cases. It might also be easier for the settlor to trust someone they know personally rather than a professional trustee.

However, this format also has drawbacks:

Trustee Misfeasance: Trusted friends and family members might also breach their duties and misappropriate trust assets if proper checks and balances are not in place.

Unfamiliarity: The trustee has a fiduciary relationship with the beneficiaries. A lay person may not have the necessary know-how to perform this job competently.

Effect of Age: There is also the risk posed by an aging trustee who may become disinterested or less capable over time but fail to recognise the need to retire from the position until a material mistake has been made.

Succession: The trustee might pass away or become incapacitated during the trust's lifetime. Hence, individual trustees are less useful when the intention is to protect generational wealth and succession.

Risks: For an individual trustee, the risks of being sued (rightly or wrongly) are difficult to mitigate. It is also challenging for a lay trustee to obtain insurance against legal claims.

Regulatory: In most jurisdictions, individuals acting as professional trustees must be licensed. Trusted friends and family members might not be suitable for licensing as professional trustees, nor might they want to be. On the other hand, without being licensed, they cannot be remunerated as professional services. As such, these individuals might not be sufficiently motivated to devote adequate time and attention to the trust.

A PTC is a company established solely to act as a trustee for a specific trust or a group of related trusts. It is typically created by the settlor or individuals related to the settlor. It does not offer trust services to the public.

A PTC offers some advantages over professional and lay trustees:

Control and Influence: A key reason for establishing a PTC is to allow the settlor and their family to retain control and influence over the trust's assets and management. The board of a PTC can include the settlor, family members, and trusted advisers, enabling direct stakeholder involvement in decision-making processes.

Flexibility: PTCs offer greater flexibility compared to professional trustees. This is particularly useful for complex assets (such as shares in operating businesses) where professional trustees might have little or no understanding of the businesses to make meaningful contributions. Additionally, PTCs might be more willing to approve transactions that a professional trustee might be reluctant to approve.

Confidentiality: A PTC maintains confidentiality by keeping trusteeship within the family rather than using third-party professionals. This is particularly appealing to those wishing to keep their financial affairs private.

Continuity: Compared to trustees who are individuals, PTCs provide continuity. Unlike individual trustees who may retire or pass away, a PTC is a separate legal entity with a potentially perpetual life. While the directors or management of the PTC may change, the PTC remains as trustee, ensuring continued asset ownership.

Cost Effectiveness: Over the life of a trust, PTCs are a cost-effective solution. While initial set-up costs are likely to be higher than using a professional trustee, the latter's fees are often based on a percentage of assets held under the trust, which can be significant over time. A PTC’s cost is self-controlled.

Involvement of Lay Trustees: PTCs are very useful if the settlor's intent is to appoint friends, family members, and trusted advisers as lay trustees. It is safer for them to act via a PTC. The PTC is the trustee, and the individuals can be directors of the PTC. As the PTC is a separate legal person, it shields the directors from direct personal liability, which is preferable to acting as an individual trustee. It is also easier for a PTC to purchase directors and officers (D&O) insurance for its directors.

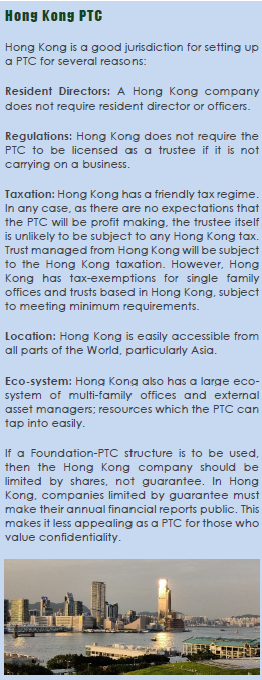

Regulatory: In some jurisdictions (including Hong Kong), trustees are not required to be licensed if they do not provide trust services as a business. Consequently, a PTC can be reimbursed solely for its operational costs related to acting as a trustee. The PTC may hire employees and directors - including friends, family members, and trusted advisers -and compensate them appropriately. This arrangement allows these individuals to be incentivised to dedicate adequate time and attention to the trust, while the PTC can continue offering services without being classified as a business.

On the other hand, a PTC has all the fiduciary obligations of a trustee. Without using professional services, a PTC may not have the necessary know-how to perform this job competently.

While versatile, a PTC needs a person or entity to hold the shares of the PTC itself (see insert regarding “Structuring a PTC”). Ultimately, this person has the power to dictate the selection of the directors and management of the PTC.

To circumvent this issue, many PTCs are created using a purpose trust to hold the PTC’s shares so that no one will be entitled to own the PTC (thus creating an orphan structure) – the Purpose Trust-PTC structure. A purpose trust is a specific type of trust established to hold assets for a designated purpose, rather than for the benefit of specific individuals or classes of people. Unlike traditional trusts where beneficiaries have rights to the trust assets, a purpose trust is set up to fulfill a stated objective.

The trustee of a purpose trust is usually a professional trustee. This trustee must act in accordance with the purpose of the trust. To ensure this is carried out, some jurisdictions require the appointment of an enforcer. The enforcer provides directions to the trustee and ensures that the trustee fulfils their duties according to the stated purpose. The enforcer is a separate entity from the trustee.

However, it is still necessary for a professional trustee to hold the PTC’s shares. This dilutes some of the benefits a PTC, as well as allowing a third-party to have influence over the PTC. To some, this may not be acceptable.

Many jurisdictions (including Hong Kong and Singapore) do not have laws permitting the establishment of non-charitable purpose trusts. For those wanting to create an orphan structure using a purpose trust, it is likely that they will have to use an offshore purpose trust.

A non-charitable foundation is a hybrid structure that combines elements of both a trust and a company. A foundation has no shareholder, but (like a trust) the assets can be used by the foundation for the benefit of another party (beneficiary). A foundation is managed by a body (typically called council) which functions in a similar fashion as a board. While it has been a part of civil law jurisdictions for millennia, it is a relatively recent introduction in common law jurisdictions.

A foundation can function similarly to a trust, directly holding assets and operating like a trust. In many cases, we argue that a foundation is a superior structure for modern succession planning. A foundation is inherently an orphan structure.

However, as a creature of statute, the characteristics of a foundation depend on where it is incorporated. Most countries that have adopted foundation laws are either in civil law jurisdictions or small offshore islands.

Civil law foundations can often be complex structures unfamiliar to many practitioners of common law trusts. On the other hand, with notable exceptions like Jersey and Guernsey, many common law jurisdictions with foundation law lack a strong reputation and history of robust private asset protection laws.

From a taxation perspective, it is increasingly important for an entity to demonstrate economic substance in the jurisdiction where it operates. It can be challenging for families based onshore to establish meaningful economic substance in remote offshore jurisdictions.

Internationally, trusts have a long-standing history, supported by a substantial body of law, including both statutes and case law, that guides professionals and regulators. In contrast, there is relatively little established case law regarding how various countries treat foundations compared to trusts. This uncertainty extends to how certain jurisdictions may view foreign foundations, particularly concerning tax and reporting obligations.

Most places that recognise foundation law also have provisions for re-domiciliation. This means that the risks associated with potential changes in the laws of a particular place can be effectively mitigated by re-domiciling the foundation to another place if there is an adverse change for the foundation.

In some jurisdictions, a foundation can be established specifically to serve as a trustee rather than owning the assets itself. This is commonly referred to as PTFs. As legal entities with full corporate capacity, PTFs can exercise all the powers and fulfil the obligations of a trustee, like PTCs. However, unlike PTCs, PTFs are inherently orphan structures, which eliminates ownership issues (or the need to create a purpose trust) in generational wealth planning.

PTFs are a great alternative to PTCs for succession planning. Apart from being inherently orphan structures, they provide similar level of control, influence, flexibility, confidentiality, continuity, and cost-effectiveness as a PTC solution.

As a result, we believe PTFs are a superior structure to a Purpose Trust-PTC structure. However, this structure has a drawback. Most countries that have adopted foundation laws are either in European civil law jurisdictions or in small offshore islands, making it challenging for Asian families to actively carry out their duties from these locations.

To maintain economic substance in these places, it is often necessary to keep a council member based in the place where the foundation is incorporated. For some, this defeats the benefits of confidentiality which led them to choose a PTC/PTF in the first place.

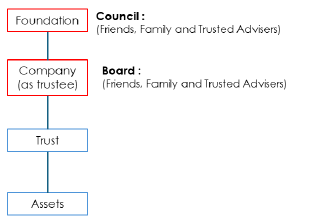

For those wishing to maintain a high level of control, influence, flexibility, confidentiality, continuity, and cost-effectiveness, and have an orphan structure, a Foundation-PTC structure is worth considering.

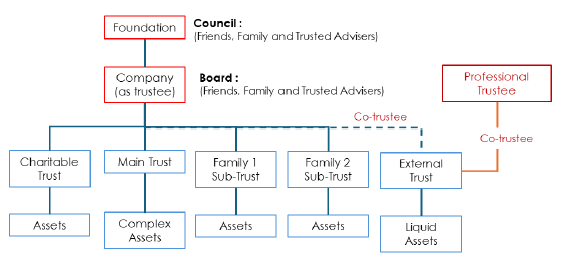

This structure works as follows:

As the foundation is only holding entity to hold the company (the PTC) which is not profit-generating (and therefore has no significant value), it is not necessary to ensure that the foundation is incorporated in the most well-regarded or best regulated jurisdiction. The foundation's charter will be relatively simple, and there should be very little (in any activities) year by year. A low-cost jurisdiction with friendly regulations will work well.

In most offshore jurisdiction, the economic substance and reporting requirements are relatively light when the foundation is only holding a passive investment. For Asian families, Labuan (Malaysia) is an ideal consideration. For South Asia, Middle East, Africa and Europe, Dubai (DIFC) is a good choice. Europeans wanting something closer to home might also consider Malta as an alternative.

The PTC can be established in an onshore jurisdiction where it is most convenient for the family members to participate in its management and operations (see insert regarding “Hong Kong PTC”). This is also where the economic substance of the PTC lies. In any case, as the PTC is expected to only operate on a cost-reimbursement basis, taxation of the PTC is not likely then to be an issue.

There is also less need to consider establishing the PTC in a well regarding jurisdiction. To the extent that law changes which necessitate the trustee to be changed to another jurisdiction, the foundation can set up a new company in another jurisdiction and liquidate the old company. Therefore, convenience and a friendly regulatory environment (which does not require licensing of non-business trustees) can take precedence over jurisdictions with well-regarded asset protection law.

The main consideration is to ensure that, if the trust is managed in where the PTC is established, that jurisdiction also has a benign tax regime for the trust's income. Otherwise, an additional layer may be needed to ensure that the assets are managed in a tax friendly jurisdiction.

The Foundation-PTC structure compares favourably against structures using either trust or foundation on their own. As against a PTC, it overcomes the need to use a purpose trust managed by a third-party. As against a foundation, it offers greater flexible for managing multiple endowments. For example, if a settlor has five children and wants to set up a succession structure for each of them and their issues, if the settlor were to use foundations, the settlor will need five separate foundations. With a Foundation-PTC structure, the PTC, as trustee, can manage all five trusts, and each trust can be tweaked to suit the specific needs of that child.

The structure also allows hybrid participation by the PTC in a professionally run trust. For example, the settlor may want liquid assets to be run by a professional trustee. Even with these trusts, the PTC might act as co-trustees to the trusts, thus ensure an additional layer of checks and balances.

A slightly more complex Foundation-PTC structure might therefore work as follows:

Other considerations

The Foundation-PTC structure also addresses some other concerns:

Legal Concerns: It overcomes concerns with foundations from less established or well-regarded jurisdiction.

Flexibility: The settlor retains full discretion to decide the proper law of the trust. It is easy to move the trust by changing the proper law if the trust law of a particular jurisdiction becomes less favourable. While it is usually possible to migrate a foundation from one jurisdiction to another, it is a more complex process.

Convenience: The PTC can be set up in a place easy for family members to effectively participate in the running of the trust. Presumably, this is why a settlor would want to choose a PTC over a professionally run trust in the first place.

Concern about Lack of Well-Developed Case Law: As mentioned, a foundation is arguably a superior structure to trust in modern succession law. However, in contrast to the robust body of law underpinning trusts, foundations are relatively new to common law jurisdictions. While countries try to give foundations similar protective provisions as trusts through legislation, there is limited foundation case law, thus giving rise to concerns among some practitioner whether courts would uphold those protections. A Foundation-PTC structure avoids these issues, as challenges to the structure by beneficiaries are more likely to occur at the trust level rather than the foundation level.

Settlors should not view PTCs as cheap substitutes to using external advisers. Serving as a trustee carries significant fiduciary responsibilities. PTCs can face various risks, particularly when operating without external advisers.

One major risk is the potential for conflicts of interest, especially when family members are directors. Personal interests may unduly influence decisions, compromising the interests of all beneficiaries. Additionally, managing trust assets across multiple jurisdictions with different tax laws can be complex; without professional expertise, the PTC may encounter tax issues and mismanagement.

While PTCs offer investment flexibility, this can lead to poorly considered decisions. Unlike professional trustees, PTCs might have greater propensity to take risks that expose the trust to losses, especially if sentimental reasons affect judgement.

Lack of external advisers can also weaken governance and administration, making the PTC more vulnerable to fraud and mismanagement. Family disputes may escalate if family members are involved in decision-making without independent guidance.

In summary, while PTCs offer advantages for wealth management, operating without professional advisers presents other risks, including mismanagement, conflicts of interest, and increased legal and financial liabilities. External expertise, while increasing cost of administration, is essential for the effective and safe operation of a PTC.

While both PTCs and foundations are great tools for succession planning, each structure has limitations. To some who want to exercise ultimate control that does not give third-party professionals any influence, a hybrid Foundation-PTC structure may be preferred, even at a slightly higher cost and complexity.

This website uses cookies or similar technologies, to enhance your browsing experience and provide personalized recommendations. By continuing to use our website, you agree to our Privacy Policy